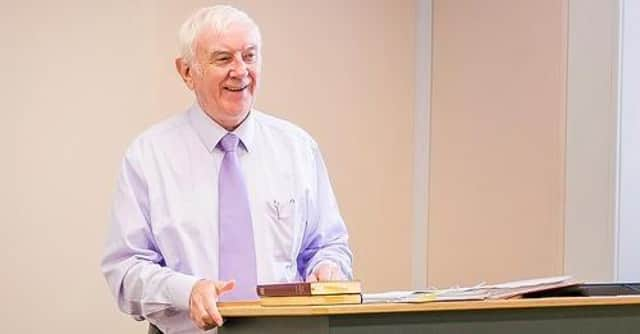

A giant of the pulpit; a master of the pen

Dr Thomas Guthrie, on hearing of the death of his colleague and friend Dr Thomas Chalmers, said, “Men of his calibre are like giant trees of the forest. Only when they are felled can we begin to truly appreciate their height.” The same could be said of the late Principal-Emeritus Donald Macleod who passed away at his home in Edinburgh on Sunday 21st May 2023, aged 82, surrounded by his family.

The same could be said of the late Principal-Emeritus Donald Macleod who passed away at his home in Edinburgh on Sunday 21st May 2023, aged 82, surrounded by his family.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBorn in Ness, in the Isle of Lewis, in 1940, Donald was blessed with an acutely perceptive mind and a phenomenal memory, gifts which he demonstrated from a young age, and which came to maturity in his career as a teacher of systematic theology and as a gospel preacher of the first rank.

After graduating from the University of Glasgow and the Free Church College, he was ordained as a minister and served in Kilmallie Free Church for six years, and Partick Highland Free Church (now Dowanvale), Glasgow, for a further eight years. His exceptional academic ability led, unsurprisingly, to his appointment as Professor of Systematic Theology at the Free Church College (now Edinburgh Theological Seminary), Edinburgh, in May 1978, initiating three decades of theological instruction which shaped his students profoundly. He was appointed principal in 1999 and retired in 2010.

Professor Macleod was unstinting in his emphasis that the College must produce preachers of the gospel. Even the highest academic ability must serve the ultimate end of producing men who could declare with conviction the love of God, the beauty of Jesus Christ, and the plight of human existence without faith in him. His lectures were always inspiring, particularly those setting out the parameters of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. These were shot through with a loving devotion to Christ, often bringing students to tears, as the present writer can testify.

As a preacher and lecturer, Donald was concerned to show that faith involves the mind as well as the heart. It was not for him an emotional attachment with little rational application, or an academic exercise with little of the joy of the Lord. Christians needed to think about what and why they believed, rather than thoughtlessly follow a tradition or practice.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdClosely connected with this emphasis, he passionately defended liberty of conscience against all attempts to interfere with it. God alone is Lord of the conscience; Christ delivers us into freedom; we are bound only by his will and word, not by the conscience of others; what is not required by the Bible cannot be demanded or made into a law for Christian behaviour. Needless to say, his commitment to the Bible as God’s revealed will was foundational to all this.

Professor Macleod’s impressive use of language came to the fore in both his preaching and writing. For many years he edited the Free Church’s magazine “The Monthly Record”, providing many thought-provoking, edifying, and informative articles, many on issues of the day in politics or national developments. He wrote a regular column for the Stornoway Gazette and was also a former columnist for the West Highland Free Press and The Observer newspaper.

His method was sometimes regarded by some as controversial, setting out his thoughts in ways designed to provoke questions, most likely a method he had been familiar with in his younger days in Christian company, when older men would deliberately debate in a way that gave the impression they were at odds with orthodoxy, but only to stimulate thought and analysis.

His years at the Free Church College produced a steady stream of articles and books, deservedly elevating him to an international reputation. He was, however, the “People’s Theologian”, as the title of a collection of writings in his honour, published in 2011, called him.For him, truth was not to be confined to elites; the Bible was for everyone, as he exemplified in his life and ministry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaking no apology for the use of theological language, he nevertheless made theology attractive, drawing people from many different backgrounds and ages, sometimes with profound effect, such as when preaching at a School of Evangelism in Stirling on one occasion (for a whole hour without notes as was his custom!), the audience of around 400 sat silently in their seats, some weeping, for a further ten minutes.

Many can also testify to Donald Macleod’s practical help and advice. Always willing to show support, sympathy and understanding, he provided counsel and comfort on numerous occasions, not least to students who had personal or family trauma to contend with.

An excellent conversationalist, Donald provided exhilarating company, with a wealth of anecdotal gems, many from his younger days in Lewis, a place which always remained close to his heart. A fluent Gaelic speaker himself, he had little time for those who disparaged the language. He was also truly pained by those who made a point of throwing off the faith of their fathers, only to replace it with a barren attachment to atheistic and secular ideologies.

In the company of Professor Donald Macleod, one was soon aware of a formidable combination of genuine humility and academic prowess. Despite all his wide-ranging talents and achievements, his own sincere approach to life was that of a man who sought only to glorify Christ and his grace, not himself. As he once wrote, “The height of a man’s Calvinism no longer impresses me. I want to know whether it’s made the man small.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat grace did make him small, in an obvious and sincere humility. That is most likely, though, the key to his greatness as a servant of Christ. As for the apostle Paul, so also Donald Macleod’s conviction was, “For to me to live is Christ, and to die is gain.”

Our sincere and prayerful sympathies are extended to Mary, his widow and their three sons: John, Murdo and Angus, as also to his brother Murdo Iain, and sister Annie Mary.

- Rev James Maciver

“I’m afraid my health has taken a serious downturn, with little hope of any improvement. Being realistic, it is now beyond me to maintain my column on a weekly basis, but I will try to contribute as strength affords. It goes without saying that I greatly appreciated the platform you gave me, but the writing no longer flows smoothly, and seems devoid of any light touch”.

Donald Macleod wrote these words on April 29th and strength did not afford for long thereafter. His passing will be felt in many quarters. For those who knew him mainly as a writer and then as a friend, the loss of his written word which challenged and informed with unfailing regularity over the decades leaves a void that will not be filled. His writing was special and his perspectives unique.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe higher pulpit of religion shaped his life, faith and beliefs but he never saw a contradiction in descending from it to communicate through the lower ones of journalism and politics, usually with a small but occasionally a large “P”. On the contrary, he was at his best as a writer addressing a wider audience when he brought the erudition of his theology to bear upon the practicalities of life and failings of society.

Applying the discipline of intellect to the headlines of the day can lead to unexpected conclusions. This ensured that Donald’s writing was never predictable. He analysed from first principles and did not shirk from where they led. If that did not always coincide with received orthodoxies, then so be it. If it attracted envy and worse as well as admiration, then that was validation of the case for original thought.

He told a funny story about being phoned by a BBC researcher who wanted him to take part in a debate on some social issue of the day. Fine, he said, but of course he would be taking the liberal side of the argument. “Oh no”, she replied in horror. “We’ve got Richard Holloway for that”. The assumption that Donald would perform to Free Church caricature always ran the risk of being misplaced.

I suppose that I, like many others in the temporal world of journalism, first became aware of him in his role as editor of the Free Church Monthly Record, a position he held from 1977 to 1990. If that journal had hitherto been read at all in the newsrooms of Scotland, it would only have been in search of pickings that pandered to the stereotypes, or could be twisted into doing so.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen they started noticing the editorials and found a man who could not only write like an angel but also held no inhibition about expressing views which were unexpectedly trenchant and often counter-intuitive. This was a period of social turmoil which cried out for positions to be taken and Donald responded without intellectual flinching while surely knowing that he was challenging certitudes deeply held by many of his readers.

The year after Donald retired from the Monthly Record, I asked him if he would consider writing a column for the West Highland Free Press. I wish I could remember more about how that conversation came about for it proved to be an inspired one. In that paper, he found a natural second home; a literate forum, addressing a mainly Gaelic, island audience with complete freedom to write about whatever he chose which he did for 24 years with style, wisdom and, of course, erudition.

When I contributed to The People’s Theologian, I spent a day in Stornoway Library reading his old columns in search of gems. The problem was that I was spoilt for choice. The consistency of quality writing was astounding; and all this through decades when, on top of his normal workload, he was regularly assailed by theological foes; endangered by false witness against him and latterly, from 1999, serving as Principal of the Free Church College in Edinburgh. And still he wrote week in, week out for that small, wider audience.

“Why”, he asked in 1994, “is there no Gaelic on Scarp? Is it because there are no Gaelic-medium schools? Or because it cannot receive ‘Machair’? Or because the church services are in English? No! It is because there are no people there. The community has been destroyed. And the same tale can be told a thousand times … The culture can only be saved by saving the economy”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany have tried to make the same point but nobody has done it so succinctly. That was characteristic of Donald’s writing. Words were not wasted and conclusions were there to be agreed with or rejected. When he wrote on matters of theology, it was not necessary to be a subscriber in order to be challenged by his train of thought or educated by the well of learning from which he drew.

While my own literary connection was through his journalism, his work as an author will prove less ephemeral. There was no danger of his last book published as recently as 2020, “Therefore the Truth I Speak; Scottish Theology 1500-1700”, becoming a best seller but it will surely remain the standard work for as long as the subject is studied. The same is true, I am sure, of his earlier contributions to church literature.

A little over two years ago, when I was asked to play a part in resuscitating the Stornoway Gazette, one of the compensatory pleasures was to ask Donald to resume Footnotes where they had left off. He did so with the same qualities as of old including, of course, a lightness of touch. The writing was great to the end.

I read John Macleod’s description of how his father, close to death, joined in the words of George Matheson’s beautiful hymn, O Love that Wilt Not Let Me Go. It was a poignant image which conveyed a serenity which only the certainty of faith can bestow, as “the joy that seekest me through pain” carried a great man and a loyal friend on his final journey.

Brian Wilson