Emigration warning in history from South Uist

This is a ‘joint’ event, linked with the memorial of the parallel departure of the SS Metagama from Stornoway. With the exception of twenty young single women, destined for life as domestic servants, the passengers on the Metagama were all young, single men who were to become farm labourers in Ontario.

However, those travelling on the Marloch were made up of family groups and they were all Catholic; this, and the further embarkations of 1924 and 1926 were strictly denominational in character. The organiser, Fr Andrew MacDonnell OSB, was attempting to establish a completely Catholic, Gaelic speaking settlement on the prairies of Alberta.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The memory of the brutality of the wholesale evictions and clearances from the ‘Long Island Estate’ of South Uist and Barra from 1848-1851 when a total of 3,500 people were duped with false promises to get on the emigration ships in Lochboisdale was one of the factors influencing the implacable opposition to emigration amongst the clergy at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th.

On arrival at Quebec, seventy of those emigrants gave voice to their sense of betrayal in a petition to the Canadian Government: ‘The undersigned further declare that those who voluntarily embarked did so under promise to the effect that Colonel Gordon would defray their passage to Quebec; that the Government agent there would send the whole party free to Upper Canada (Ontario) where, on arrival, the Government agents would give them work, and furthermore grant them land on certain conditions. The undersigned finally declare that they are landed in Quebec so destitute that, if immediate relief be not afforded them, and continued until they are settled in employment, the whole be liable to perish with want’.

The other major factor which determined the opposition of the clergy to emigration was the actual availability of land on South UIst. Their attitude, voiced eloquently before the Napier Commission of 1883 by the 28 year old parish priest of Daliburgh, Fr Sandy MacKintosh, was that there was plenty of land for everyone if the large farms were broken up and each was given enough land to make a living from.

On the other side of the fence was Lady Gordon Cathcart, the Estate owner. For her, emigration was a necessary tool to bring the population down to the level which the land could support and to rid the place of crofters, who would only ‘exhaust’ the land. She sponsored a couple of small, ‘supported’ emigration schemes to Saskatchewan on land belonging to the Canadian Pacific Railway. She didn’t mention that she held a significant shareholding in the company!

Advertisement

Advertisement

By the time the Marloch sailed in 1923 all the farms on the Long Island Estate had been broken up into crofting townships or were on the way to being broken up. After the First World War came economic depression and real poverty as the country tried to move from a ‘war economy’ to a ‘peacetime’ one.

The parish priest of Daliburgh confessed to the Bishop of the Diocese of Argyll and the Isles that he didn’t know how many of the people managed to live; eight of the families on Eriskay had received assistance from the Bishop’s Fund in that year. As far as the priest was concerned, it was a case of ‘emigrate or starve’.

Nationally, there was a strong sense of ‘emigration fever’ and a sense of a moral obligation to assist the colonies and dominions with settlers; colonies and dominions which had so generously helped the ‘old country’ during the war.

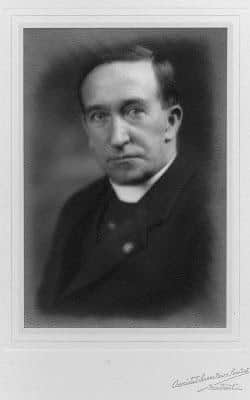

The organiser of the emigrations from South Uist and Barra, Fr Andrew MacDonnell, was born in Invermoriston and spent his boyhood in Kintail. His family roots were in Lochaber and he was a close connection of the MacDonalds of Cranachan, the distillers of Ben Nevis whisky, amongst other things.

Advertisement

Advertisement

He became a monk of Fort Augustus Abbey and was ordained a priest in 1896. A Gaelic speaker and a Gaelic scholar, he spent the first five years of his priesthood at the Abbey. In 1903 he travelled to Vancouver Island to try to find ‘positions’ of employment for orphan girls and boys. By 1915 he had signed up as a chaplain to the Canadian Seaforths, part of the military force from that Dominion then moving to Europe. He received the Military Cross for gallantry.

For some reason, which isn’t clear, after the war he became a paid emigration agent for the Canadian Government. His task was to recruit candidates suitable for emigration to Canada. He determined their suitability, both moral and financial.

One of his chief ‘selling points’, if such were needed, in enlisting the support of Bishops and priests was to tell them that his plan was to found an entirely Catholic community of Hebridean settlers on the prairies. The island people, he maintained, were ‘innocent as the day is long’ and would be liable to lose their faith if exposed to the wiles of the secular world. Partially by employing this tactic, he gained the support of the Archbishop of St Andrew’s and Edinburgh, the Archbishop of Glasgow, the Archbishop of Edmonton, and the Bishop of Argyll and the Isles. Early on, he appointed Fr Donald MacIntyre, a native of Kilpheder, South Uist, and a parish priest in Barra as his second-in-command.

The Canadian Emigration Department was never made aware of the strictly denominational character of the ‘package’ which MacDonnell was selling! At the very least, MacDonnell was double dealing.

Advertisement

Advertisement

He landed at Liverpool on Tuesday, 14th June, 1921, and in his report to the Emigration Minister he tells of the fruits of his labour, made all the easier because he had ‘softened the people up’ to the idea of emigration to Canada a couple of years before when he had visited. Over 800 people had attended his meetings in South Uist and Barra, but he remarks that those who want to come do not have the means to pay. MacDonnell insisted many years later that the original plan had been to bring as few as 18 families to Canada as a sort of ‘advance party’ with each of the families having to produce capital of $1,000 before being accepted.

The organisation was chaotic and no-one seemed to be in charge. The emigrants had to sell their goods before they left and then had to undergo medical examinations before embarking. Several failed and they and their families had to return to the croft where everything had already been sold!

The clergy in Uist and Barra were all enthusiastically behind the emigration scheme of Fr MacDonnell - but there was one exception: the Fort William born, Fr Willie Gillies. He wrote to the Bishop that he had initially been in favour of the emigration. However, he was highly critical of the lack of organisation; there was no sign of MacDonnell. Information came ‘through the grapevine’. He worried that the islanders would be ‘left in the lurch’.

But his criticism of MacDonnell appears to have been based on previous knowledge of his way of operating: ‘Personally I do not care much to the hand that presumably guides these matters and this not from personal feelings, but from sad knowledge of former failings’.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Despite the chaos which surrounded the departure, the SS Marloch set sail for Canada. Half of those who travelled on her had no money at all. They were enticed by the promise of free land and loans in advance.

45 parishioners from Ardkenneth and ninety six from Bornish parishes made up a significant part of the group but people came from Benbecula and Barra also.

Fr MacDonnell’s idea was sound enough. The settlers would go to Red Deer, Alberta, and they would be housed at a former Indian school called ‘Ard-moire’ – a sign of its new identity. There they would learn the basic skills needed for farming on the prairies, which were very different from the skills needed to farm a small croft in the islands. When sufficiently prepared, they would then be given plots of land to rent with loans available for equipment. This was not what they had been promised as far as the settlers were concerned.

Difficulties ‘dogged’ the emigration; 100 of the children contracted measles and a doctor and nurse had to be hired. There were other expenses which had not been catered for: small loans for transportation, repairs and renewals on the buildings. The settlers complained that the houses which they had been given had not been constructed with seasoned wood and had not been insulated.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Two further emigrations took place in 1924. In total, between April 1923 and December 1924 MacDonnell brought 1200 settlers to Canada. The optimism of these figures belies an underlying weakness in the whole scheme.

In 1925 the Assistant Deputy Minister at the Department of Immigration and Colonisation wrote looking for the money which had been advanced to the settlers. Only a tiny percentage of the loans advanced to settlers for their passage to Canada had been repaid; many had moved on to other parts of the country and to the United States, and those remaining had refused to give their names. Those whom the Department managed to get in touch with claimed that they would repay their loans when the promises which had been made to them were kept!

The famous Fr John MacMillan went out to become the chaplain to the settlers in 1924, but once he got there and had heard their complaints, he formed them into an organisation to fight for their rights. They petitioned the Canadian Government through the MP for Red Deer, Alfred Steadman.

This was all too much for MacDonnell. He had MacMillan called back home, blaming him for things going so drastically wrong, claiming that when he came home in 1924 MacMillan was so keen to sell the Canadian Emigration scheme that he ‘over-egged’ the pudding, saying that there was a farm for everyone whereas what was actually on offer was cottages, farm labour, and, perhaps after a year or two, a farm.

Advertisement

Advertisement

At the end of February, 1926, MacDonnell was able to announce that land had been purchased at Vermillion, Alberta, for the formation of a new colony, to be called ‘Clandonald’. There were three partners to the deal: the British Government, the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society.

The Canadian Pacific Railway ‘took responsibility for disbursing monies invested by the British Government in stock equipment, and by both the British Government and the Society in cottages and barns and undertook to repay the debt pro rata to the investors.’. Lady Gordon Cathcart, although getting on in years, was still a shareholder in the Canadian Pacific Railway, the company which was underwriting loans to settlers from the crofting communities of the islands of which she was the notorious owner!

In late Spring 1926, 48 Hebridean families, who had been working on training farms at Red Deer, settled on farms at Clandonald.

Eleven families from Ireland arrived, followed by 41 families from England and Scotland. Each family was promised a farm of 160 acres, 10 acres of which would be ‘broken in’ before they arrived. The ‘breaking in’ of part of the land, to allow the settlers to sow a modest crop on arrival, never happened nor were the promised agricultural implements provided. The promised stock was not provided. The settlers had to buy stock on the open market; prices were highly inflated because of their desperate need. Payment for all the loans which they borrowed was to be over a thirty year period.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The church was opened in 1926, named St Columba. A convent quickly followed and then a Catholic school. But what had been given as promises had never been realised. This, added to the severity of the prairie winters, made the first few years in Clandonald years of hardship. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that it became a prosperous and comfortable place to live.

Fr Andrew MacDonnell kept ‘chasing’ the representatives of the Canadian Government to put things right, but the Government ignored him other than in 1937 awarding him an MBE for services to Canada. He returned to Fort Augustus Abbey in 1956 and died in the Bon Secours Hospital, Glasgow, in 1960. He is buried at Fort Augustus.

Such was the level of complaints and divisions caused by the lack of organisation and breach of promises in relation to the Canadian Emigration schemes that Bishop Martin, the Bishop of Argyll and the Isles, who had been an enthusiastic supporter of them in the early days, issued a pastoral letter in 1927 stating that the Church would not support these schemes in the future, and the following year he sent a letter around the priests banning them from taking any part in them.

Perhaps the settlers experienced shame at their being inveigled into the Emigration scheme, which turned out to be a flop, or perhaps it was a sense of bitterness, rancour, embarrassment, and disappointment that led to the whole matter not been spoken about until now.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Added to these sentiments was the sense that the betrayal had been carried out, wittingly or unwittingly, by a priest, one of the emigrants’ own. In the words of one commentator, ‘they believed that, whether he meant to or not, he had in fact abetted their landlord, Lady Cathcart, who for several reasons wanted them off their crofts’.

The community of South Uist Estate will mark the centenary of the 1923 Marloch emigration with the unveiling and blessing of a monument to all the emigrants from the ‘Long Island Estate’. This is the kind of gesture of expurgation of bitter memory which can only be accomplished with community ownership. Expurgation of bitter memory can only take place by looking reality in the eye and moving on.

It has always been the case that there are ‘snake oil salesmen’ who offer the allure of a better life, a promised land, to the poor and the vulnerable, whether they be a on the Mexican- USA border, the English Channel coast, or here on the islands, selling, in this case, emigration to Canada. The poor are always open to exploitation by the unscrupulous.

The memorial at Lochboisdale, representing an emigrant ship, should be a memorial, a reminder, and a warning.