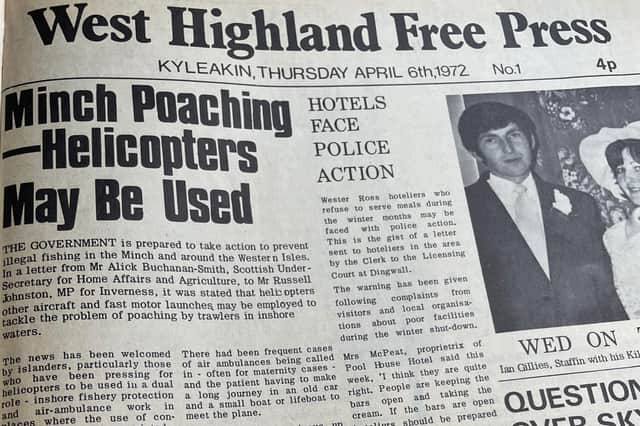

The journey that brought to life a local newspaper

It was founded by four friends who met at Dundee University; Jim Innes, Dave Scott, Jim Wilkie and myself. I might have let the 50th anniversary pass without nostalgia if it had not been for a Facebook post from my old friend, Father Colin Macinnes. “I have often said,” wrote Colin, “that the West Highland Free Press did more to prepare the Islands and Highlands for the 21st century than any other single institution or social force”.

Shortly after, I had a long lunch with the Runrig “boys” – as we all then were – and conversation went down the same route; the impact the Free Press had by taking on long dormant issues and by adopting, in word and deed, the values of the old Highland Land League summed up in: “An Tir, An Canan ‘sna Daoine”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe story began really on Arran where I had a fringe role in a short-lived newspaper called The Islander, while a student. That venture failed but the idea of an island paper remained with me. In these carefree days, the idea offered an attractive alternative to making an early entry into the more formal jobs market.

I had edited the student newspaper at Dundee but needed some training. It was my good fortune to win a place on Britain’s first post-graduate journalism course at University College, Cardiff, run by a great man, Tom Hopkinson, who had been war-time editor of Picture Post and then of a multiracial magazine in South Africa. He greatly encouraged the idea of the Free Press.

There were only 16 on the course and one who became a lifelong friend and great journalist was Donald Macintyre. Don had, or so he said, come into a small legacy and put £2000 into the Free Press. In return, he was made the fifth director. That was our only capital.

We placed an advert in the Oban Times seeking premises on Skye – ideally, a house to serve as both home and office. There were half a dozen replies but discussions with the first few owners did not last long, neither the stated purpose nor my long hair going down particularly well.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe final option was in Kyleakin; a house close to the ferry called Coille Bhurich which had been inherited by two sisters, Kay and Flo Reid. Kay had been matron of Broadford Hospital while Flo was soon to retire as headteacher in Kyleakin. They had no particular plans for their recent inheritance – a fine five-bedroomed house.

Better still, Kay and Flo were politically active as stalwarts of Skye Labour Party and the Isle of Skye Peace Centre. When I explained the nature of our project, they identified with it completely. The terms of rental were quickly agreed. To have chanced upon such an empathetic pair of women in Skye who happened to have a house to rent was a life-defining stroke of fortune.

We set a target of the first week in April to launch the paper. There remained, however, the small question of how it would be printed. Inquiries around Kyleakin revealed old stable buildings behind the King’s Arm Hotel which were lying empty and a deal was done. We knew a printer who was keen to join the adventure and was duly recruited.

Don’s £2000 was to be invested in equipment and the printer was entrusted with scanning Exchange&Mart for suitable purchases. He identified a machine called a Vari-Typer and a small litho press which would produce pages smaller than ideal but big enough to look like a real newspaper.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGordon the printer, Dave and I set off for an industrial estate in Walthamstow where this near-useless junk was acquired. The Vari-Typer had been a great innovation in its time. Unfortunately, that time was 1937 when it was introduced in New York as an electronic advance on the typewriter with “the ability to print in a variety of typesets in various sizes”. It was a ponderous machine which slowly produced uneven text, as we would soon discover.

I set about establishing outlets for the paper, having decided the circulation area should include the Inverness-shire islands from Harris down to Barra. It was only later that we tried to make inroads in Lewis, particularly after local government reorganisation brought the islands together.

Throughout my student years, I promoted entertainment as a holiday earner and this became a source of subsidy for the Free Press. My first visits to Stornoway were in that role and I had a habit of dropping into the Gazette office for a chat with Donnie Macinnes. One day, Sam Longbotham, the Gazette’s managing director, joined the conversation and asked what I was planning to do after university.

In all innocence, I replied: “I’m thinking of setting up a paper on Skye”. Major Longbotham adopted his full military bearing and declared: “If you start a paper on Skye, we shall fight you and we shall destroy you”. I was a bit startled but also from that moment determined that the Free Press would indeed have a presence throughout the Western Isles!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were many more shops than today and I went round them all, seeking orders. A dozen here, half a dozen there. I recall doing my sales pitch to the elderly custodian of the tiny Post Office in Drinishader. He listened patiently before replying: “Son, the last paper we sold here was the Bulletin”. Since that estimable journal ceased to exist in 1960, this was not encouraging.

However, like all others, he agreed to take some copies and see how they went. When, a few weeks into publication, the order from Drinishader increased from 12 to 15, I knew we had arrived.

Macintyre’s was the only newsagent in Portree and was clearly going to be important. I explained about the new paper to Hamish Macintyre. He looked doubtful and said: “Ach well, send us 100 copies”. Hamish must have seen my face fall and he asked: “Is it sale or return?’. When I said it was, he came back: “In that case, send as many as you like”. For many years, MacIntyre’s sold 1000 copies each week and Hamish paid the bill – often a life-saver – on the spot, without taking a day’s credit.

Meanwhile, Dave Scott was working away on the advertising side and receiving a remarkably good response. The first issue would carry a full page advert from our old friends, The Corries, and inexplicably, even in these less regulated times, from Benson & Hedges. Advertisers as diverse as the Glenlight Shipping Company and, to my delight, Inverness-shire Conservative and Unionist Association joined in the spirit of the launch.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver in the stables, however, doubts were seeping in. The Vari-Typer turned copy into type at an alarmingly slow pace via a clanking keyboard. I was focused on putting the content together and it was only in the early part of our first publication week I had to face the fact it simply was not going to happen if we left it to a print-shop assembled on the basis of hopeless over-optimism.

At this point, with a very real chance of the West Highland Free Press never seeing the light of day, Jim Wilkie became the key player with a cool head. He set about phoning round printers in Inverness to find if any would help us out. Astonishingly, he struck gold.

Eccleslitho was a small printing firm located in what had been the church hall of the FP congregation in Inverness and an offshoot of a larger letterpress printer. The businesses were run respectively by twin brothers, Donald and George MacAskill. Both in later life would become ministers of the Associated Presbyterian Church.

That initial conversation between Jim and Donald secured a short term fix. However, it was the longer term relationship which Jim secured that gave the Free Press a future. The agreement was that Eccleslitho would do the whole job. We would keep the first £100 of revenue to live off and they would take the rest. It was an astonishingly generous arrangement which allowed us to keep body and soul together while they took all the risk on how much, if anything, they would be paid. And it was all done on trust.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn later times, it was often written that the Free Press was launched with money from the Highlands and Islands Development Board. In fact, I had written to the HIDB seeking support but, probably because it sounded so implausible, I did not even receive a reply (though they later faced down political criticism to become supportive when the paper moved to a home of its own in Breakish).

The reality was that the paper started entirely on £2000 which had gone largely on buying useless printing equipment and was saved from instant extinction by the goodwill of two Free Presbyterian brothers who placed faith and trust in a bunch of long-haired radicals they had only just got to know. The Macaskill brothers rank high in the list of those to whom I have owed a life-long debt of gratitude.

The politics of the Free Press were always defined by the stories it covered, rather than by any ideological mission. First and foremost, it was a local paper which shed light and challenged authority. It also fed into other great initiatives which for a time brought questions like land ownership, depopulation, historical awareness and Gaelic’s future to the fore. In turn, these drew me into political activism which eventually yielded the opportunity to do at least something about them.

Fifty years on, the paper still exists, it provides jobs, it has an editor of good Kyleakin stock who understands what it has always been about. The old order changeth, but that is a set of results which, if offered, the founding fathers would have grabbed with both hands. And the need for good local journalism with a radical edge is undiminished.