Two sides of the same Celtic coin

However, they do serve the purpose of encouraging reflection and perspective – in this case about why policies have largely failed to achieve the outcomes described in the title. And also why so little effort is made to learn from elsewhere, particularly our closest neighbour in Ireland.

These edited extracts try to put these questions in context. They also suggest an explanation if not an answer.

THE STATE WE LIVE IN

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI don’t need to tell anyone in Ireland about borders and how they are the products of politics and history, rather than being predestined. We are all, to lesser or greater degree, defined and confined by the state into which we were born or in which we have chosen to reside. This makes it possible to be very close together geographically but very far apart in other respects.

If I had been able to define the state in which I live, it would run from the Butt of Lewis to the Ring of Kerry, with no borders in between. That would have been a perfectly rational basis on which to define a state if history had worked out differently. You just have to look at the map of these islands in a slightly different way to see the potential. Our Celtic state could have formed a spiritual, cultural and linguistic continuum, as it once almost did. And a lot of other problems and borders might have been avoided.

Unfortunately, history worked in other directions and the western seaboard became the outposts of both states and empire – divided by borders, facing largely in different directions, kept apart by religions, raped by landlordism, the people and cultures dispersed to the four corners of the earth. It is shared history that cannot be undone but, even now, might be ameliorated.

The principle is simple – that people who are so close together should not be so far apart. I am certain that we have a lot to learn from each other. By sharing these experiences, our peripheries and the cultures that cling to them might be strengthened, however marginally.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course the challenges of maintaining life and vibrancy in peripheral places is by no means restricted to Scotland and Ireland. Where there are success stories to be learned from, we should have been studying and adopting them long ago. We have not been sufficiently interested in looking elsewhere and certainly not to Ireland. Yet Ireland should all along have been a natural partner in the 20th century commitment to maintaining people and culture in peripheral areas.

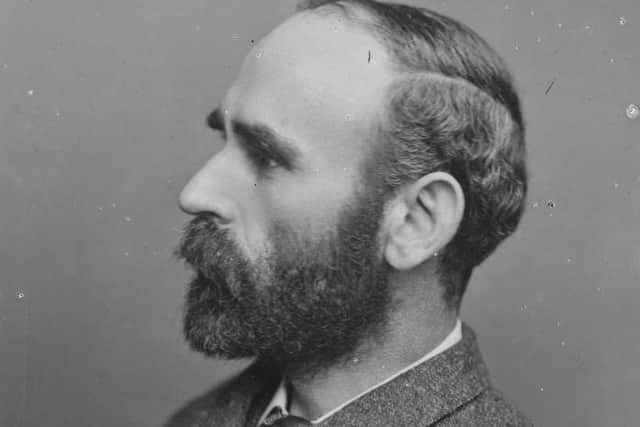

MICHAEL DAVITT

One figure in history who understood this very well was Michael Davitt, founder of the Irish Land League. For him, the struggle of the crofters movement in the face of eviction and emigration, was the other side of the same coin that afflicted rural Ireland. Davitt saw support for the crofters’ movement as a bridge into Protestant Scotland and hence Ulster through a common cause, breaking down the barriers of religious suspicion.

Wherever he went, Davitt emphasised the shared background of Scots and Irish. According to the Glasgow Observer in 1887, when Davitt met with John Murdoch, a leading figure in the crofters’ movement, “so loud and hearty was the cheering that the mountains as well as the buildings echoed in celebrations of a meeting with Celt with Celt”. In Skye, the crofters petitioned this Irish radical to become their Parliamentary candidate.

As a footballing aside, it was Davitt who influenced Celtic’s founders to adopt that name as one which brought the two peoples together, in a club that was from its outset open to all, rather than retreat into a name and identity that would suggest Catholic exclusivism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSadly, Davitt’s vision of Celtic unity – whether in the slums of Glasgow or the Gaeltacht communities of the north and west – pretty much died with him and was soon overtaken by far stronger forces of division while our two sides of the same coin grew ever further apart.

Different states, different politics, different religions. Yet the logic of co-operation still lay in the fact that, for all these differences, the outcomes continued to be so similar for our Scottish and Irish peripheries in terms of out-migration and, with it, the steady marginalisation of language and culture.

GLENCOLUMBKILLE

The West Highland Free Press was, in its day, a bit of a journalistic phenomenon and there was a regular flow of potential emulators, occasional detractors or the merely curious, who dropped in to our base on Skye. One of them left behind a small black booklet with a cover which bore the maxim: “Better to light one candle than to forever curse the darkness”.

I eventually got round to discovering that it was not a religious tract, but an account of the story of Glencolumbkille in County Donegal, and the extraordinary transformation it was undergoing under the guidance of the parish priest, Father James McDyer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had returned from years ministering to the Irish community in England to find that his leadership was desperately needed at home. Glencolumbkille was in a state of backwardness, poverty and decline. McDyer started to shake it up, driving through the concept of a multi- function co-operative – a co-chomunn – which would collectvely bring in electricity, work the land, take over the local hotel and initiate economic activity.

By the time I became aware of it, the Glencolumbkille example was showing impressive results and the Co-chomunn movement was spreading in the west of Ireland. Having finally got round to reading the pamphlet, I hot-footed it to Donegal and also to Inishmaan, which was another early participant in the co-chomunn movement. The parallels with our own periphery were inescapable and the concept of multi-function community co-operatives based on local needs was revelatory.

To cut a long story short, Father McDyer and Tom O’Donnell, who was then Minister for the Gaeltacht, agreed to come to the Western Isles to explain the co-chomuinn concept. The Highlands and Islands Development Board got behind it and for a few years, community co-operatives sprang up throughout the Western Isles – an Irish inspired idea which, for a time at least worked well and of which significant legacies remain today.

In some cases, the much later community land buy-outs had their origins in the co-chomuinn which gave communities the confidence to realise that self-help was possible. It had indeed been better to light one candle than forever curse the darkness; just a pity that more candles did not follow.

SMALL NUMBERS

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChange is inevitable and desirable. But how can change be achieved, how can population be retained, and at the same time maintain the cultural identities that make these places special? To me, that is a challenge which should be grasped by policy makers with enthusiasm and commitment, rather than treated as a peripheral nuisance they would rather be without.

I do not know enough to judge which end of the spectrum Irish policy making is at, but I am acutely aware that Scotland’s is based on endless lip-service which is used to disguise a fundamental lack of interest, far less priority for the economically and culturally fragile periphery.

One symptom of mutual failure lies in the positions of Scottish and Irish Gaelic/Gaelige in their remaining bastions. While the headline numbers are vastly different, with 1.7 million Irish citizens claiming to speak the language, the decline of the Gaeltacht areas is far more parallel to the Scottish experience.

The official Irish Gaeltachts have contracted to around 70,000 people of whom only 20 per “retained substantial Irish vernacular use”. In other words and in broad terms, both Scottish and Irish Gaeltachts consist not of millions of people, or hundreds of thousands, but of a few tens of thousands on whom the survival of each as living, community languages depends.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese are micro communities requiring micro solutions. The question is how best to deliver them. The statistics, in terms of both depopulation and linguistic marginalisation, suggest that nothing to date has worked very well. So it might be thought prudent to consider another option which would be to devolve policy down to the lowest possible levels in order to facilitate the best possible outcomes.

In researching this lecture, I came across an academic article by Dr David Meredith headed: “Is rural Ireland really dying? What do the facts and figures tell us”. It explained: “We need to ensure that an appropriate spatial scale is used in future to inform policies, particularly those directed at peripheral and rural areas. The question of whether rural Ireland is dying is complicated and requires nuanced geographical analysis … Previous research has shown that the scale of analysis is key when examining population loss. If we want effective solutions, we need to start using appropriate scales of analysis”.

This exactly reflects how population statistics in Scotland have been used to mask the reality of continuing decline in our most peripheral areas. The bigger the area, the better the story from an official point of view. Successes are proclaimed and headlines achieved. But dig deeper into the geographical nuances and the realities emerge.

To a significant extent, the transfer of population takes place within the larger geographical unit – e.g. the Highlands and Islands – as families move from village to town, because they cannot find land or house or work; the three prerequisites for remaining in a peripheral places. If they stay in the region, they are used as statistics which are claimed to represent success but, in terms of peripheral population, actually reflect the critical failure.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe fundamental problem of population retention in peripheral areas is that almost no policies are initiated with that objective in mind. National policies are formulated with minimal regard to how they will play out in places for which they were not designed. Not only are these made remotely but each is contained within its own individual silo when the geographical nuances of peripheral areas cry out for them to be integrated into co-ordinated approaches to meeting micro challenges.

NO PEOPLE,NO LANGUAGE

For far too long, the blindingly obvious bottom line of language survival was ignored by official Boards and bureaucracies – that without work and homes to live in, there are no people and without people there is no language. A language policy that is not based on this fundamental economic and social truth is totally divorced from reality.

Scotland owes a debt to an Irish academic, Conchúr Ó Giollagáin and his colleagues for producing in 2020 a study called “The Gaelic Crisis in the Vernacular Community” which called out official policy towards Gaelic which for the past 20 years been heavily bureaucratised and directed towards increased learner numbers while remaining Gaelic heartlands continued to decline.

The work of Ó Giollagáin and his colleagues disturbed the official narrative and was not welcomed in government circles. However it energised debate about policy and has resulted in some shift of resources towards the core Gaidhealtachd areas and adoption by the Labour Party of a Gaelic policy closely aligned to Ó Giollagain’s findings. A Languages Bill is promised in the Scottish Parliament.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe referred to “the maintenance of an illusion of adequacy vis-à-vis Gaelic policy in the face of language loss”. O Giollagain added: “The current language policy may rest on an undeclared assumption that the demographic and spatial limitations of the existing group of speakers is not extensive enough or politically significant enough to justify policy attention and thus expenditure on troubling and complicated societal issues”.

And that “undeclared assumption” really is the nub of the matter for language and peripheral areas more generally. It summarises what I have observed over the decades as both journalist and politician.

From the perspective of remotely located policy makers, there are not enough people “to justify policy attention and thus expenditure on troubling and complicated societal issues”.

That is what must be challenged and changed, just as it has been all along.