Why is it so hard to just say sorry?

During an interview on Times Radio on 24th August, he admitted to me that he had not said sorry. This was the same day the Scottish Government announced a public inquiry into its handling of the public health emergency. It was also the same day that Scotland recorded its highest ever number of new daily coronavirus infections – although that record has been beaten most days since.

There are no shortage of mistakes on record already, and much has been written about the lack of preparedness of the government, the appalling decision to return hospital patients who had not been tested for Covid back to care homes, the exams fiasco, miscommunication to the most vulnerable people in Scotland, low PPE stocks for health workers, a separate contact-tracing app that doesn’t cross borders into the rest of the UK, the First Minister missing six Cobra meetings as she criticised the Prime Minister for missing five. A team of Edinburgh University epidemiological scientists concluded that had lockdown been introduced in Scotland two weeks earlier than March 23, then 2,000 coronavirus deaths could have been prevented.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the SNP won the election in May, the Scottish Government said it would set up a public inquiry within the first 100 days of re-election. That target was missed by ten days, according to the opposition parties’ calendar which counts from election day – May 6th. The Scottish Government disputes the date saying its 100 days concluded on 25th August. Let’s not tie ourselves in this particular knot…

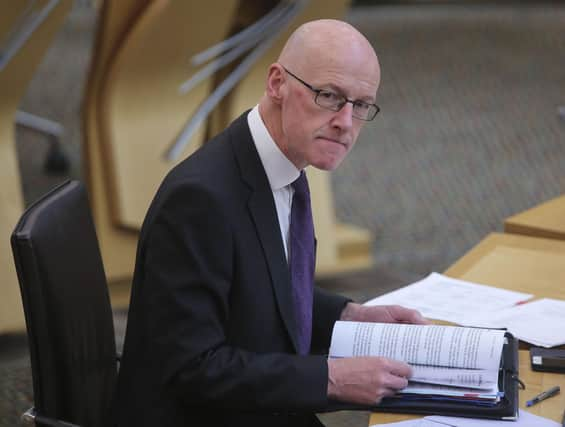

I put some of these pandemic mistakes to John Swinney. He wouldn’t answer directly, saying that the inquiry would decide what it would look into and assess what action was required. I can understand his strategy, in spite of my frustrations at his lack of commitment to defining the scope of the inquiry.

Conversations with politicians, particularly those of such seniority in government, are vitally important. They give us a chance to hear, or read, what the strategy, or thinking, or wisdom – or otherwise – is behind decisions being made that affect us all. They give politicians a chance to connect, communicate and converse, for them to convey a message and for us to learn and analyse. Their words are important.

After going back and forth, Mr Swinney confirmed he had not apologised, but said that the Scottish Government has apologised many times. The issue with his defence is that apologising down a camera lens at a press conference is a different type of apology to an apology offered in a room, face to face with other people, whose relatives have died and who have experienced the worst effects of this pandemic first hand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmy Ebesu Hubbard, a professor of communications at the University of Hawaii says, in the context of a corporate apology for failure: “If there’s no clearly stated apology, that communicates that the company doesn’t care about the customer, or that there’s no longer even a relationship.” Consider this, then in the realm of politics where failures are already obvious, and indeed have been admitted. Consider it in the context of, for example, the Deputy First Minister sitting with families who have lost family members throughout the pandemic. Professor Hubbard’s analysis would suggest, whether this is true or not, that the Deputy First Minister doesn’t care about those families. That’s why it was important to ask him.

I received several Tweets after the interview with various people suggesting the interview was “self-serving” and I should “go back” to my usual programme slot on Early Breakfast. Someone else said I “appeared to want a 'gotcha' moment from the interview” and “didn't get one.” Make of it what you will, I’m open to criticism always and will always consider it. But words - and apologies - are important.

Let us add to this the thoughts of Yohsuke Ohtsubo, a psychologist at Kobe University, who has studied the science of making apologies and the effect this has for more than a decade.

He says: “My research shows that it’s the cost to the offender that matters...The cost communicates the sincerity of your apology. If you really value the relationship and you want to restore that relationship you can pay the cost, because you value the relationship more than the cost."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy point here is that apologies from politicians are essential. As Scotland’s inquiry gets underway, and as politicians look to placate those affected and commit to learning from their mistakes, they must also state their apology – corporately, and individually.

They must work to restore – or build – trust. Their apology must be costly to convey their sincerity, if they truly value their relationship with the electorate. That’s why it was important to ask the Deputy First Minister if he had found the word “sorry” in his vocabulary that day. That’s why it was shocking to hear that he hadn’t.