Arandora Star and the lessons that live on

Yet the story of the Arandora Star lives on. In Ireland recently, I noticed a report about a memorial being raised to one of its victims. There are annual commemorations in diverse locations, not least the Tuscan community of Barga where many of the Scottish-Italian community originated.

The Western Isles does not remember the Arandora Star any more or less than countless vessels on which its sons perished. However, some form of memorial might be appropriate for the themes which surround the loss of that ship, torpedoed off the Aran Islands on July 2nd 1940, are of both universal and current relevance, worthy of reflection as well as recollection.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe particular poignancy for our own islands was that the men buried in Hebridean cemeteries included both captors and captured. More than 700 men died when the ship was torpedoed by the Germans with 1500 on board – mainly German, Austrian and Italian internees, along with their guards from the Lovat Scouts and Royal Dragoons. The presence of Lovat Scouts guaranteed that when bodies came ashore, a few would be washed up close to their Uist homes.

Even at a time when the horrors of war were becoming all too familiar, the sinking of the Arandora Star gave rise to some public outrage, though it seems unlikely that the primary concern of most Britons was the fate of people who bore Germanic and Italian names. It was the wholesale nature of internment and transportation which appalled.

Major Victor Cazalet, one of the MPs most critical of mass round-ups, told the House of Commons: ''There has been a tremendous public demand for the internment of practically everyone whose family has not lived here for 100 years, in complete disregard of the individual merits of the cases concerned.''

I first became aware of the story through the diaries of Compton Mackenzie, who was living on Barra when some of the bodies were washed ashore. Alongside his many other involvements, Mackenzie was a great Italophile. When the connection was made between the Arandora Star’s human cargo and the bodies on Barra’s beaches, he described it as “the culmination of the despicable hysteria about fifth columnists”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe policy of mass internment had developed in 1940 against a background of threatened invasion and paranoia about the arrival of Continental refugees. Home Office Minister, Osbert Peake, told the Commons that many feared for their safety. ''Temporary internment'' had become ''the most humane thing to do''. Winston Churchill put it more succinctly, in his infamous injunction to ''collar the lot''.

That policy extended to Stornoway and the late Mary Scarramucia recalled: “My parents were taken away from the island during the war. The police here were against them taking my father away. They took him to Inverness. Eventually they sent them to an internment camp on the Isle of Man; he was there for four years and my mother was sent to Pitlochry”.

Her father was among the fortunate ones. As the number of internees swelled, the Government put pressure on other Allied countries to take some of them. Fatefully, the Canadians agreed to accept 4000 internees and the Arandora Star was chartered to carry the first consignment across the Atlantic.

Time was short for identifying the people to be deported. Germans and Austrians in this country had been classified A, B and C. Those in A category were supposedly active Nazis and captured merchant seamen. Supposedly, all the 473 Germans and Austrians earmarked for the Arandora Star came under these headings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere had been no such classification of the Italians. In theory, the 717 put on board the ship had been identified as members of the Fascist Party. But subsequent events demonstrated that this was far from the reality. The Arandora Star sailed from Liverpool on June 30 and was torpedoed two days later.

When I first wrote about the Arandora Star, I spoke to Dino Bonati, who was 16 when his father, who owned a café near Eglinton Toll in Glasgow, was taken away. 'We lived in Calder Street and at three in the morning, after Mussolini declared war, a policeman came to the door. He knew my father from the cafe and said: 'Alfie, I'm sorry I have to take you into jail. They'll probably let you home tomorrow'.''

Instead, he was interned at Milton Bridge, near Edinburgh. Dino recalled: ''There was a double electrified fence, and we could just shout through it. It was a terrible sight -- all these old Italians out of cafes, living in tents and plodding through muck. We couldn't give the food parcels personally and I just left with a promise to go back next Sunday.''

It was the last time Dino saw his father who, with hundreds of other Italian ice cream men entirely innocent of political subversion, ended up on the Arandora Star. A month after the ship went down, Alfonso Bonati's family received a letter from the Home Office apologising for the fact he had been wrongfully interned.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe true horror was hinted at by David Kirkwood, the Glasgow ILP MP, when he asked a Minister to confirm those on board included ''prisoners of war and internees mixed up with Fascists and anti-Fascists, Nazis and anti-Nazis''. Eight days after the sinking, the Commons debated it for the first time. MPs queued to give examples of wrongful detention, followed by transportation to their deaths on board the ship.

On August 15, 1940, Compton Mackenzie received a letter from an old friend who was vice-chairman of the Italian Internees' Aid Committee. She wrote: ''I see that a number of bodies from the Arandora Star have been washed up on Barra. I wonder whether among them there have been any who have received Catholic burial?”

Mackenzie replied: ''The body of one Italian was washed up on the long beach toward the Atlantic behind our house. This was identified as Enrico Munzio by his card which showed that he had been a tenor, singing probably in the chorus at San Carlo and over here for the BBC and at the Coliseum.

''As soon as permission was received from the various authorities he was buried in the ancient burial ground of Eoligarry by Dr Trainer of Bearsden . . . Your task must be a poignant one indeed, but I am thankful to hear of something being done that may mitigate in the eyes of Almighty God this detestable crime which burdens the nation's soul.''

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLater, a Lovat Scout sergeant visiting Barra gave Mackenzie an account of what had transpired. ''There were not nearly enough boats and after the torpedo struck the Scouts and the Royals jumped overboard with lifebelts. Nobody had shown the Royals how to use a lifebelt; the result was that nearly all of them broke their necks when they hit the water. I hear the words of that sergeant now: 'It was a bit peculiar see all those poor chaps bobbing about in the water with their heads wobbling all over the place.'

''Many of the German internees had scrambled on board some of the boats filled with Italians and pushed them into the water to drown. The behaviour of those responsible for that panic about fifth columnists still makes me wince to recall.''

The Clyde Maritime website carries a full account and in 2012 Malcolm Morrison contributed information about Hebridean connections. One of the military guards, his 21 year-old nephew, Trooper John Connelly was washed ashore on the coast of Mayo, where he is interred. His mother, Christina MacKay, was from Linaclete. According to Mr Morrison, “the South Uist War Memorial, for the Gerinish area commemorates a ‘Private Ian Connely, Lovat Scouts’ and it has been assumed this is the same person”.

Trooper William Colquhoun, also 21, was washed up on Barra and interred at Nunton Old Cemetery on Benbecula. “He was the son of Duncan and Mary Ann Colquhoun, and grandson of Catherine MacEachen, all of Creagorry, not far from his final resting place”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

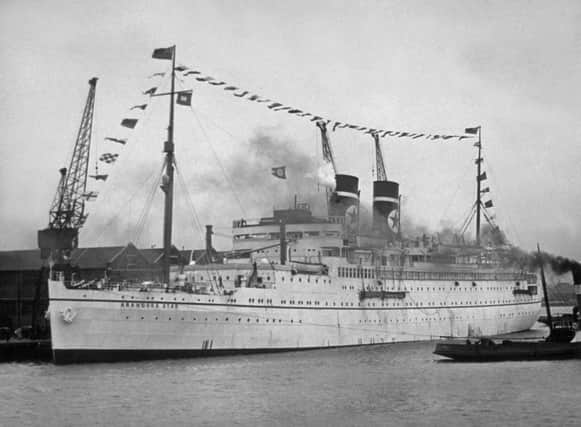

Hide AdA third Lovat Scout was Corporal Roderick Matheson, a native of Baleshare, North Uist. “Following the sinking,” wrote Mr Morrison, “he was in the water for nine hours, clinging to wreckage. After training in Canada as an expert skier and Alpine Climbing Instructor, Corporal Matheson lost his life in action whilst serving in the Apennine Mountains and is interred in the Rome War Cemetery. Another Military Guard on Arandora Star, Roderick MacSween of Gerinish, was rescued.” At least two of the crew were islanders – Finlay MacKay, an AB from Benbecula, and the bosun who was Neil MacLeod from Luskentyre in Harris. Neil had been on the Arandora Star in her pre-war days as a luxury cruise ship, sailing in the Mediterranean and Caribbean. He was married to Annie MacKay, the aunt of Donald John MacKay of Luskentyre who remembers many conversations about the Arandora Star before Neil died in 1967.

“He was exposed to oil inhalation when he was in the water and never fully recovered”, says Donald John. “He would describe the barbed wire the prisoners were kept behind and how completely unnecessary it was as far as the Italians were concerned. They were all complete gentlemen who had been rounded up because of their names. He always regarded that as very wrong”.

The story of the Arandora Star is no more awful or unjust than many others. But it might cause us to reflect afresh on the folly of judging any individual on grounds of nationality and of how humanitarian instincts are swept away in the frenzy of war. These are lessons that a tangible reminder of the Arandora Star’s story in the Western Isles could help to impart.