The Gaelic psalms and Gospel harmony

The New York Times obituary related how he “fashioned an unlikely career in jazz as a French horn player and toured the world as a musical missionary in the acclaimed Mitchell-Ruff Duo while maintaining a parallel career at the Yale School of Music”.

That other side of Ruff’s work was as a musicologist, digging deep into the origins of the music which had dominated his own childhood in the churches of racially segregated North Carolina during the Depression.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEventually, it was this dimension to Willie Ruff’s career which, in the latter stages of his life, brought him into close contact with the Hebrides and, in particular, the Gaelic Psalm singing tradition which he came to believe was closely linked to the music of his own black America.

This contention helped to propel the Gaelic Psalmody tradition into the consciousness of a far wider international audience and also created human connections which involved, for more than a decade, a series of transatlantic exchanges, extraordinary concert performances, academic debate and more than a little hostility towards Willie Ruff for the theory he propounded.

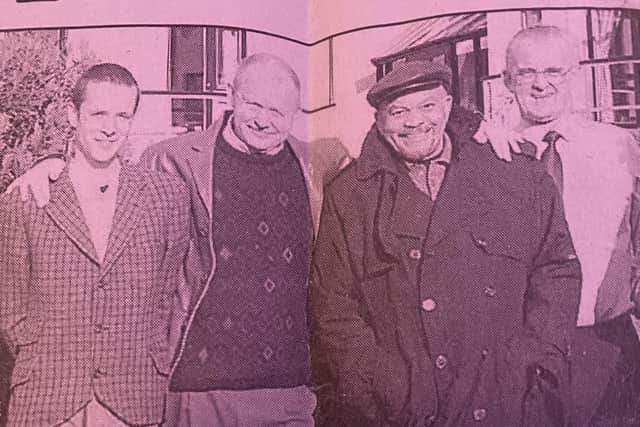

On hearing of Ruff’s passing, the Lewis musician Calum Martin, who became his collaborator in researching these musical connections, signalled his own sense of loss by posting: “I was so sorry to hear of the sudden passing of my good friend and amazing human being, Willie Ruff, a true musical genius and intellectual giant”.

The roots of that friendship lay in the theory which Willie Ruff embraced that the way in which Gaelic Psalms are sung was taken to America by Gaelic speaking settlers from the 17th century onwards and became a major influence on the development of black Gospel music and how it is performed. Initially, this was in the Cape Fear area of North Carolina and from there the Influence spread.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was controversial because it challenged the deeply held – and politically important – conviction among black Americans that their cultural roots and forms of expression derive from Africa, the continent from which their forebears were seized and traded into slavery.

According to his own web-site, Willie Ruff was first introduced to the idea that some Afro-Americans in remote areas of the Deep South still sang Psalms in Gaelic by his friend Dizzy Gillespie, who was a native of South Carolina.

While this certainly piqued his interest, it was a chance encounter with a Baptist congregation that finally brought him to Scotland, according to Calum Martin.

There, he heard an unusual form of “line singing” and in the conversation that followed about where this came from and where it survived, there was mention of the Hebrides. “He was on the next flight over”, says Calum. “He said that as soon as he heard about it, he had to come over and check it out”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe timing proved propitious since he was soon pointed in the direction of Calum who, coincidentally, was in midst of producing two Gaelic Psalmody CDs, to raise funds for Bethesda hospice. These recordings were made in Back Free Church, in October 2003. From there, Willie Ruff’s conviction that the two musical genres were close cousins intensified.

For at least one local resident, the appearance of Willie Ruff in Back Free Church was remarkable. Peter Urpeth recalls: “As a music journalist with a particular interest in Black American music and its origins, I had long known Willie Ruff’s work as a performer and educator. I should say that I was astonished, but not at all surprised, when he was suddenly exploring the Psalmody traditions of my local church in Back which had survived in that congregation and community for so long”.

For generations of worshippers in the Presbyterian tradition, “line singing” of the Psalms, led by a precentor, has been as natural as the air they breathed or the language they spoke. While it had been widely recorded and admired, the idea of Gaelic Psalm singing being a progenitor of Gospel music in Black America was not something that had previously arisen.

The debate which this opened up was not one that Gaeldom initiated. When it arose, it drew attention to the uncomfortable fact that some Gaelic-speaking settlers, like others, were involved in the slave trade. From a black American perspective, distinctions were unlikely to be drawn between sources of “white” influences, Gaelic or otherwise, on their music, when rejecting the general thesis.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeaving aside these delicate considerations, it was immediately attractive to Calum Martin and others to continue exploring the possibility of connections and the relationship through Willie Ruff blossomed. The following year, 2004, a 14-strong group of Psalm singers from Lewis travelled to Alabama to put the theory to the test.

Calum Martin said on returning: "It was an amazing trip all round. We arrived in the church having not really met them before, and just ended up doing our own singing. We didn’t know whether there would be a connection at all but you could see there was a connection, although they didn’t understand the language. Then they did their music and the commonality was clear."

By then, the Willie Ruff theory was attracting considerable media and academic interest and had been embraced by other musicians, notably the late Martyn Bennett. Its next manifestation was a concert as part of Celtic Connections in January 2005 when The Scotsman reported:

“On Friday a group of Gaelic psalm singers from the Hebrides will share a bill with black singers from the deep South who, they believe, are keeping a variant of their tradition alive. After singing separately, the two groups will sing together, uniting the traditions for the first time in 200 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is the conclusion of a remarkable journey from the Isle of Lewis to the deep South and back, driven by jazzman Willie Ruff. He believes that "precenting the line" - the traditional unaccompanied singing of psalms in Gaelic in the Presbyterian churches in the Hebrides - is the ancestor of "lining out", still practised in black churches in the South and, therefore, that Gaelic psalm (salm) singing lies at the root of all black American music”.

After that, there were conferences at which these theories were subjected to academic scrutiny, first in Scotland and then at Yale University where Willie Ruff was a Professor of Music.

The 14 Psalm singers from Lewis with their precentor were met by him at the airport and conveyed to the conference venue by two stretch limousines. “It was typical Willie”, says Calum.

The Willie Ruff web-site recalls: “In 2005, Ruff, a renowned jazz musician and ethno-musicologist. organised an international conference at Yale, bringing together a few of the almost extinct congregations that still practice the line-singing tradition. Clergy members, journalists, documentary makers and scholars from a broad range of disciplines were invited to New Haven to listen, record and share their perspective.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The Free Church Psalm Singers of the Isle of Lewis, Scotland; the Indian Bottom Old Regular Baptists of South -eastern Kentucky; and the Sipsey River Primitive Baptist Association of Eutaw, Alabama, came to perform a service they shared but that each had adapted over generations to their own idiom”.

All that may have taken the music of island churches far beyond its usual setting but also enhanced recognition and respect within the global firmament of Christian worship and musical expression.

Sometimes, however, Willie Ruff went into overdrive. In a 2005 interview with Ben McConville for Scotland on Sunday, he really pushed the boat out: “We as black Americans have lived under a misconception. Our cultural roots are more Afro-Gaelic than Afro-American. Just look at the Harlem phone book; it’s more like the book for North Uist.

“We got our names from the slave masters. We got our religion from the slave masters and we got our blood from the slave masters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“None of the black people in the United States are pure African. My own great, great grandparents were slaves in Alabama. My grandmother’s maiden name was Robertson. I have been to Africa many times in search of my cultural identity but it was in the Highlands that I found the cultural roots of black America”.

The profile which Willie’s theory was attracting started to attract rebuttals, both academic and political. For academic heavyweights whose specialism was the origins of black music in America, this new theory was seen as an unwelcome heresy.

One such expert, Professor Terry Miller of Kent State University, Ohio, who had studied “the practice of ‘lining-out’ in both Hebridean and Afro-American traditions” wrote a lengthy rebuttal under the heading “A Myth in the Making: Willie Ruff, Black Gospel and an Imagined Gaelic Scottish Origin”.

Calum Martin says: “The whole thing started to blow up in the press. Poor Willie was given a real roasting. He was getting it from both sides. There were black Americans who were completely opposed to the idea that the roots of the music were anywhere other than Africa.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Then the Scots language lobby pitched in. Billy Kay (a Scots language campaigner) was vehemently opposed to this idea that Gaelic had anything to do with it. They hated the idea that anything came from Gaelic and said that if there was any Scottish influence, it must have come through Ulster-Scots”.

“Really”, says Calum, “all Willie was highlighting was that everything is a melting-pot and the language and religion which Gaelic settlers had brought to North Carolina has influenced the music of black America. But then so did a lot of other things, which I’m sure he wouldn’t have disagreed with either”.

It is indisputable that,from the mid-18th century, tens of thousands of Gaelic speakers settled in great numbers in North Carolina and other parts of the south. Many were accompanied by tacksmen who staked claims to land holdings in their new country.

As James Hunter wrote in “A Dance Called America”: “Men of this type had not soiled their hands with manual labour on their farms or tacks in Scotland. Nor did they personally work the land which they obtained on coming to America, entrusting that task to their immigrant Scottish Highland servants or to black slaves who, this being eighteenth-century North Carolina, could be very easily bought”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were doubtless many Gaels who identified with the plight of the slaves. Equally there would have been those who participated in the trade.

Either way, it seems likely that their own culture exerted some influence over the people they lived among over the course of 200 years.

“The fact is”, says Calum Martin, “that nobody really knows”. And that really is the truest statement of all.

In the absence of Willie Ruff, it seems unlikely that anyone else will push the “Afro-Gaelic” theory with quite such conviction – but that does not mean he was entirely wrong.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPeter Urpeth says: “Many interactions occurred, many variations developed and the Psalmody tradition was a strong line in that process.

"To acknowledge that history, to trace the surviving embers of a culture that was not allowed to have its own name, was to honour and to cherish these traditions. That was Professor Ruff’s heartfelt agenda – one of music, community and humanity”.

One certainty is that for a decade, Willie Ruff helped draw international attention to the cultural and spiritual phenomenon of how Gaelic congregations continue to worship through the Psalms. On a hard-headed note, that did no harm to sales of these CDs made by Calum Martin in Back Free Church, which have now raised £300,000 for Bethesda.

It is unlikely on current trends that any future researches will still be based on a living tradition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCalum Martin says: “As with everything else in life, things change. When I recorded the first two CDS, there was a congregation of 400 in Back. When I recorded volume three, a few years ago, I only managed to get 150 people into the Town Hall”.