Fifty years on – an Iranian shop steward and a Lewis work-in

Nowhere was this form of industrial action more unexpected than at a factory on Parkend industrial estate in Lewis which had been established with public money to produce Harris Tweed jackets.

But it happened – and, on the 50th anniversary of the great Lewis work-in, memories of the event remain strong. Within families, there is still pride in the fact that the mainly female workforce had the courage to take a stand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRhoda Macdonald, whose mother was one of those involved, says: “I’m still amazed at the women’s militancy. Good on them!. So much for those who thought island women were reserved and submissive!”.

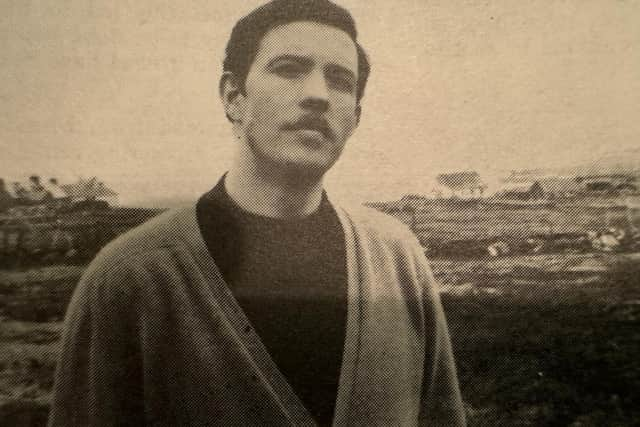

National interest in this unexpected outpost of worker resistance was heightened by the fact that the shop steward, who became its public face, was an Iranian-born follower of the Ba’hai Faith, a placid religion which eschews involvement in politics and conflict.

Speaking from his home in Toronto this week, Enayat Ráwháni recalled his reluctance to take on the role lest it should be incompatible with his religious beliefs; but also his determination to support fellow-workers “at a time of financial stress and very high unemployment”.

The 50th anniversary brought back Enayat’s memories of the March day he arrived at the factory to find his fellow workers gathered outside. “The doors were locked and there was a notice saying the factory was closed but everyone wanted to get inside and carry on working as before”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA few days later, they occupied the factory having broken through a door with the intention of continuing to produce jackets while expecting the Highlands and Islands Development Board, which had invested heavily in the business, to find a buyer who would carry it on. That never happened.

It was not the HIDB’s finest hour. Basically, they were conned by a shyster and when the venture came to grief, their objective was to bring an episode which attracted widespread publicity to a rapid conclusion. Enayat Ráwháni travelled to Inverness to meet them but, he recalled: “They were only interested in ending the embarrassment. They were not interested in finding a buyer”.

The company was called Samuel MacDonald Ltd but one of the few certainties about its owner was that his name was not Samuel Macdonald. Believed to be a former captain in the Rhodesian Army whose real name was Mackechnie and who was married to a Norwegian, he admitted to having adopted the “Macdonald” name only for the purpose of approaching the HIDB.

In Lewis, the Board had by then pinned hopes on Harris Tweed as an engine of economic revival, in the absence of inward investment. The main thrust of this strategy, a bizarre plan to locate weavers in factory units operating power driven looms, later collapsed in acrimony.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, it was not difficult to see why a proposal which added value on the island to Harris Tweed fabric and at the same time created significant employment ticked the Board’s boxes. They invested £28,000 – in today’s money about £320,000 – in Samuel Macdonald Ltd.

The venture attracted a lot of interest and support. There was little work available at that time, particularly for women. A machine sewing class was established at Lews Castle College and most of the women who took part went on to work for the new company when it opened at Parkend in 1972.

By March 1974, the government of Edward Heath was in its death throes and industry was on a three-day week to conserve power because of a miners’ strike. Times were hard and rumours spread that “Samuel Macdonald” was planning to close the Parkend factory permanently.

Relations between boss and workers had never been cordial. They regarded him as an incompetent chancer and he claimed they were slow to pick up skills. There had been a previous dispute over Macdonald’s refusal to provide chairs for the workers to sit on during tea-breaks. Such incidents persuaded them they needed a union, hence an approach to the Tailer and Garment Workers Union. Enayat Ráwháni – a graduate in business management – said at the time that it had long been obvious the company was seriously mismanaged and heading for difficulties.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said that “if representatives of the HIDB who visited the factory had taken a look at what was going on instead of going straight to Mr Macdonald’s office, they would have found out long ago that the firm was in trouble”. When the factory closed, he said, there were 30 workers but over two years previously, there had been a turnover of 89.

As uncertainty grew, a delegation of the workforce offered to work for nothing until a buyer could be found. “Macdonald” told them to get out. Their fears were realised when the notice appeared on the door announcing closure, with immediate effect.

One of the women involved was the late mother of Calum Macdonald, who subsequently became Labour MP for the Western Isles. Calum recalled this week: “I was a student in Edinburgh at the time and only knew what I was reading in the press.

“I do remember hearing that when the police arrived after they had broken into the factory to start their work-in, my mother – being older and a pillar of the church – was pushed to the front to tell them that they had found the door already open, which she claimed to be the only fib she ever told in her life”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe work-in lasted for only “two or three days”, Enayat Ráwháni recalls. When “Samuel Macdonald” appeared and found the factory occupied, he ripped the telephone from the wall. When the occupiers tried to re-start work, they found the all-important patterns had been removed by their employer. For good measure, he ordered the Hydro Board to cut off the power supply.

That effectively brought the work-in to an end though efforts by Enayat Ráwháni to find a buyer continued for several weeks. There had been an expectation that Pitlochry Knitwear with which “Macdonald” was rumoured to have a family connection would step in but this never materialised. The council’s development officer, Robin King, gave strong backing to Enayat’s efforts but with the HIDB washing its hands of the matter, it was the end of the road.

As reported at the time: “Attempts were made to have electricity restored to the factory so that work in hand could be finished. But once the firm was officially in liquidation, the Highland Board – who might have guaranteed to pay the electricity bills – felt they could not intervene directly”.

A meeting of creditors was held in Stornoway’s Acres Hotel on 29th March 1974 when debts of £59,000 (around £780,000 in today’s money) were revealed. Many local firms, including the Harris Tweed mills, were left with no prospect of getting their money and the workforce were owed holiday pay. Meanwhile, “Samuel Macdonald” had done a runner!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTom Clark – whose mother-in-law was one of the workers – recalls: “Macdonald was our next door neighbour when we first came to Sheshader in 1974. He had a wife called Atla - Norwegian I think - and two young children.

“There was a rumour he was an undischarged bankrupt who had been given start-up money by the HIDB and that they hadn't conducted proper checks. He was described by his staff as ‘a plausible rogue.’

“One morning, shortly after settling into our house, we woke to find he had done a moonlight flit with his family, landrover, dogs and all, on the overnight ferry. I think they headed back to Norway.

“Donna's mum got the list of creditors as she, along with the rest of his workers, was owed money. I was shocked to see he hadn't even paid the Coffee Pot for the chocolates he gave his staff for Christmas!”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdENAYAT RAWHANI had arrived in Lewis with his wife and two toddlers in 1970. Two more children were born on the island. He was a “pioneer” for the Ba’hai Faith, seeking to expand a small presence which had existed on Lewis for almost 20 years.

While the Ba’hais have suffered persecution in Iran, the choice to leave his native country – which was still under the Shah - was Enayat’s own, to further his studies in the UK. Once in London and graduated, the church offered him two possible “pioneer” postings – Lewis or Northern Ireland. In 1970, it was not a difficult choice.

He recalled this week that when the workers at Samuel Macdonald Ltd decided to join the Tailor and Garment Workers Union, they needed a shop steward and asked him to represent them. He only accepted after being assured by the union that they did not seek conflict and believed in co-operation.

Events quickly took a different turn and Enayat felt a duty to his fellow workers. “Many of them were working very hard to take care of their families. They needed these jobs. Financially, it was a really dire time and I felt very sad about this”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “The factory was producing very good sports jackets which were being sold for high prices in Scandinavian countries and in some leading stores in the UK. The business could certainly have succeeded if it had been properly run. We tried very hard to save it”.

After these hopes evaporated, Enayat was approached by a local businessman, Louis Bain, to help him run a company called Lewis Gas Services. “A wonderful man”, says Enayat. He worked in this role until 1977 when he and his family left the island.

By then, he said, early suspicions about their presence had been overcome and they had many good friends in Lewis and throughout the Western Isles.

Calum Macdonald recalls: “My mum and many others were great friends with them. I remember them visiting our house frequently and being fascinated by them”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRhoda Macdonald says: “Mum loved sewing – she had a beautiful old Singer Treadle machine and made most of our clothes when my sisters and I were wee. She was absolutely delighted when she got the job at Samuel Macdonald’s, although she struggled a bit at the beginning with the industrial sewing machines! She loved the work and the camaraderie and formed lasting and close relationships with many of them, including the Persian ladies”.

The reason for the Ráwháni family’s departure was that Enayat had first been elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Ba’hai Faith in the United Kingdom and then became its secretary general, which necessitated being based in London.

After ten years,,he wanted out of city life and moved to Canada – reverting to the role of Ba’hai “pioneer”, this time in the Yukon and Alaska, travelling among very remote communities which received few visitors. Thereafter, he and his family settled in Vancouver and latterly in Toronto where he remains very active in Ba’hai affairs and runs a speciality tea business.

Iran to Toronto via Lewis and the Yukon has been quite a life’s journey – and the role of shop steward leading a factory occupation on a Hebridean island was a milestone which still features strongly in the gentle Ba’hai’s memories.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnfortunately, the attractive idea of tailoring Harris Tweed on the island, as well as producing the fabric, disappeared along with “Samuel Macdonald” and has never been revived on any scale.

Ian Angus Mackenzie, former chief executive of the Harris Tweed Authority and now chairman of Harris Tweed Hebrides, says: “It was always the holy grail to have the jackets made on the island, adding value and creating more employment.

“It’s been talked about from time to time since the Parkend episode but has never come to anything. The setting-up costs would be high, the skills would need to be developed and it would be very difficult to compete on cost.

“Maybe with modern technology it’s possible – but I wouldn’t like to be the one who tried it!”.