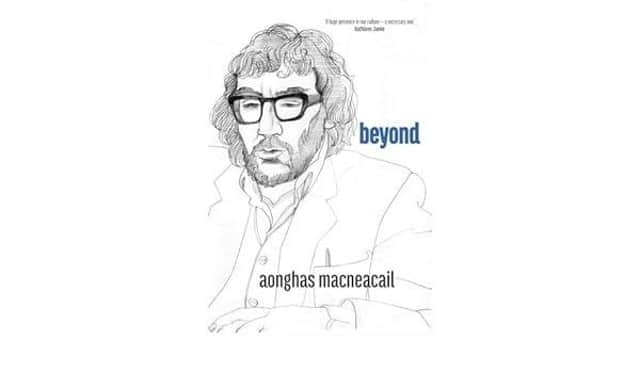

Posthumous collection is Skye bard at his best

How utterly fitting, that these two creative and cultural giants should herald a collection of Aonghas’ English poetry, from an archive that “contains thirty years worth of unpublished material”, a project undertaken and approved during the pandemic, with poet Colin Bramwell.

In the introduction, he quotes Aonghas as saying: “The first poem that I ever wrote was in English – I only began to write poetry in Gaelic once prompted. In fact it was an invitation to be writer in residence at Sabhal Mor Ostaig in Skye, that, in effect, turned me from being an English language poet who wrote occasionally in Gaelic, to being predominantly a Gaelic poet for a period of years”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe remember him principally as a Gaelic writer, from his modernising influence on Gaelic poetry, to journalist, songwriter, broadcaster and so much more. With as many names (Angus Nicolson, Aonghas Macneacail or as we Gaelic speakers knew him “Aonghas Dubh) as the languages in which he wrote – English, Gaelic and Scots – they all emanated from the same root.

His themes were universal, whether that was about the places he called home, or his contemplative observations on Nature, to saluting the seasons and of course, love. I was more familiar with his Gaelic writing, and “Breisleach”, immortalized by the ethereal vocals of Karen Matheson, to my mind one of the most beautiful love songs in modern Gaelic, as angst ridden as any contemporary equivalent.

In this final collection, there’s a playfulness that often appears in his work, and one that hints at joy, as if the journey or pursuit of love itself is worth the pain and torture. The same is true when he observes nature and the seasons, or when he is musing on the limitations of life.

Gerda Stevenson, his wife and fellow poet says in the foreword: “His poetry was his passport, and took him far beyond these shores – to Japan, the USA, Canada, Russia and to many countries across Europe”, but it also took him into the hearts of those who heard his words.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn ‘missing’ he reflects on the words of his young daughter: “do you miss your Mum…and I, grandfather old, reflect how you learn to accept, let go….yet there’s still a place in memory for moments, the smile, the frown, the face that told so much in silences”. Such a powerful transaction in such few words.

He speaks of a world we recognise, and of a people who carried the pain of their history in stoic silence. He writes of schooldays and the exciting innocence of youth, as though he were looking through the classroom window at his young self.

In “reel to rattling reel”, he recalls the mobile cinema arriving at the school – “then reel to rattling reel the story was spun for our knock-kneed rows of breaths held in on backless benches” and then “we performed our acts of valour in the playground during dinner-break”, each verse eloquently evocative, and written to be read out loud to another “knock-kneed row of breaths”.

He remains on familiar territory for my own favourite “from a shoreline in Skye” as he almost whispers the words for fear of disturbing the natural inhabitants: ‘I watch, through cracked binoculars, a silent heron winging low across the still clear sea and, with its own reflection, make a pair of clapping hands applaud its own existence’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe is the quiet observer capturing what we have all seen and forgotten, until he opens our eyes and reminds us: “a doe, dips light, uncertain feet among dry shingle”, as clear as though it were a picture on a page. He paused to look and record, while we walked on. At the Kelvingrove Museum, there is “an archaeologist of love”, where a young couple ‘speak a language without words’, before he entreats us to look at ‘dusk scene from a high window, glasgow’, where ‘those tower blocks are filing cabinets stacked families on concrete shelves’…and further on, ‘down beside the unseen river……a cormorant becomes a living spire salutes the night folds into sleep’.

If he creates a soundscape, he also brings olfactory appeal: “when you smell the motion of bluebells, when you hear a hoofmark honeycomb after long summer grasses are scythed’ is how he opens “flags”, addressing how we “plough’ the land to make cities of industry… ‘you cannot ask the paving stones to be a mountain again” feels like a rebuke.

When he fixes his compass on nature and the seasons, he becomes the theatrical architect, creating the backdrop for the opening scene of that silent first fall of snow, in ‘snowhere’, .. ‘it seems at first so hesitant, but fills, as if a breath spread out across the land’… ‘and when we wake, the world’s put on a bridal shirt….no walker’s stride observed along the bandaged hill”. He finds the impossible – colour in a white landscape, both literal and emotional.

This is a joyous book that speaks to us all, a landscape lullaby, and a reflection of a life lived and celebrated. It should inspire us to do the same.