How a BCCI apocalypse was quietly avoided

It remains a salutary tale of how events in far-flung lands can impact on the most peripheral corners of our own islands. The story of BCCI belonged in the drug capitals of the world and the wealth-soaked sheikhdoms of the Middle East. But it also washed up here, out of nowhere.

For 20 years, Bank of Credit and Commerce International had been trading as an ostensibly respectable organisation, owned by the ruler of Abu Dhabi, run from Pakistan with the declared aim of becoming the first competitor from a less-developed country to the dominant American, Japanese and European banks.

Advertisement

Advertisement

That ambition not only created its obvious client base but also made regulators extra cautious of challenging it. BCCI operated through two companies – one in Luxembourg and the other in Grand Cayman. Its lack of transparency had been worrying regulators for years and the Bank of England refused to allow Abdul Hassan Abedi, the charismatic Pakistani who ran it, to set up a separate UK company.

Nonetheless, BCCI opened 44 branches in the UK, drawn in huge numbers of individual clients mainly from Asian communities and created a specialism in offering favourable terms to local authorities which trusted it with their money in a decade of austerity and cuts. Whatever the misgivings, BCCI remained on the approved list of banks to do business with.

And then, one day in July 1991, the music stopped – to which I will return.

Comhairle nan Eilean was by then 17 years old. Starting life as a completely new authority, it had been fortunate in the early calibre of councillors and quality of senior officials – a line-up which would have graced far larger authorities.

Advertisement

Advertisement

By 1991, only Donnie G. MacLeod, the director of finance, remained of that original close-knit, successful team and in common with every other director of finance was forced to think creatively when facing the challenges of shrinking services and budget cuts.

As Sandy Matheson, convener in the 1980s, recalls: “In my opinion then and only reinforced since, the genesis of the whole disaster lay with the Thatcher government from 1979.The impact of the Poll Tax and the ever growing reduction in Rate Support Grant were the root causes.

“Thus the council – and we were not the only one stung by BCCI – had to maximise returns on all banked receipts including the annual drawdown for revenue purposes. This was done quite legally by seeking the maximum interest on deposits and even borrowing to gain extra income. The error of judgement was that Comhairle nan Eilean put all its eggs in one basket breaking a cardinal rule to spread the risk”.

If the internet had been available 30 years ago, a session on Google would have raised concerns. But it did not exist. So the council’s investment eggs had continued to go to BCCI. They even borrowed from elsewhere to put more into BCCI for the higher rate of return. And then the music stopped.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The fact £24 million was lost was, by any standard, sensational. It was a drop in the bucket compared to BCCI’s creditors as a whole. But the fact one of the smallest local authorities in the UK had lost the greatest amount was extraordinary.

Instantly, the Hebridean clichés were dusted down in the newsrooms of Britain. Money galore,.. dour Presbyterian islands … naïve islanders on Europe’s edge … the full battery of ridicule and denigration. Calling a Day of Prayer and Humiliation added to the hubris.

The £24 million equated to half the Comhairle’s annual budget so the media bristled with predictions of 1000 per cent poll tax increases (yes, it is that long ago); draconian service cuts and mass redundancies. None of which happened – and that is perhaps where the real, largely untold story begins.

A SOLUTION EMERGES

There was no way the government of the day was going to commit to bailing out the BCCI victims as Prime Minister John Major quickly made clear in the spirit of the times.

Advertisement

Advertisement

But Scotland, perhaps then more than now, is a political village and there was often a shared willingness to find solutions to genuine problems – which this certainly was. What followed was a masterclass in quiet diplomacy to find an outcome that worked for everyone.

Critically, Comhairle nan Eilean had made no enemies. It had been a well-run, non-political authority with plenty friends in the right quarters. The trick lay in finding a solution that did not involve the Treasury and did not contradict the Prime Minister’s stated position.

Calum MacDonald, the islands’ Labour MP, came home that weekend to find “senior officers and councillors in the convener’s office, in a state of shell-shock”. The strain on these people was incredible. Rev Donald MacAulay resigned with dignity as Convener. Donnie G. MacLeod would lose his job at the end of the day but the urgent task was to find a solution.

Calum recalls: “I knew very little about local authority accounts but 'Donnie Finance' gave me an excellent crash course - literally! - and handed me an enormous computer printout which had the Council’s myriad revenue and expenditure streams.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“An item called Special Islands Needs Allowance caught my eye and it was explained that it was a payment from the Scottish Office to the three island Councils in which Shetland got the lion's share, Orkney next and the Western Isles the least.

“Digging around, SINA turned out to have been introduced many years before to compensate Shetland Council as they were the biggest losers when oil and gas pipelines were de-rated. The Government couldn't call it the ‘oil and gas derating allowance’ because they would have had to compensate lots of local authorities pro-rata. So it was dubbed the Special Islands Needs Allowance and a small amount was allocated to us and to Orkney to complete the disguise.

“The appeal of SINA was that, potentially at least, it could be reviewed, updated and re-allocated by the Scottish Office without having to ask the Treasury for extra cash and without breaching the Government's repeated refusal for compensation.

“It offered a glimmer of hope and so I went to see Allan Stewart, the relevant Scottish Office Minister. With his mutton-chop sideburns and hard Thatcherite views, Stewart's public image was as a Victorian throwback, but though he liked to play up to the image, he was not a fool. In fact, he rather liked doing things off-piste, as it were, and was willing to help if a solution could be found behind the backs of the Treasury.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“My next conversation was with Jim Wallace, the MP for Orkney and Shetland, as they would be losers in any re-allocation. By pure chance, he was lobbying the Scottish Office on another, unrelated rating issue. If the Scottish Office would agree to their request, Shetland could accept a SINA review.

“The deal was done, an ‘independent’ SINA review was commissioned and recommended a new allocation that mysteriously gave the Western Isles exactly the amount needed to cover the cost of the new borrowing it took on to replace all the money lost in BCCI.

“To maintain the discretion, the new SINA was announced between Christmas and New Year to minimise press attention, and I promised the new Minister, James Douglas-Hamilton, not to make any public connection between it and BCCI, a promise I've kept up to now.

“I am delighted to pay him and the late Allan Stewart a belated tribute for their role in digging us out of that awful hole, with the result that, in the end, we didn't suffer a single compulsory redundancy or cut in service. Indeed, as interest rates started to go down sharply soon afterwards and have stayed down most of the time since, we may even have earned a wee surplus from SINA”.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The BCCI liquidators eventually got back about 80 per cent of the money lost. Once again, this worked well for the Western Isles due to changes in the dollar exchange rate over the next 20 years. In 2011, when the last instalment came through from the liquidators, with all the debt repaid, the islands had actually made a small profit from the BCCI affair.

DAY ZERO

So what about the day the music stopped – July 5th 1991? Years later, I got another perspective on this, from the man who quite literally closed down BCCI.

The tipping point came when the Luxembourg authorities tried to shift regulatory responsibility to the Bank of England. There had been plenty rumours about BCCI but this brought matters to a head. In March 1991, the Bank commissioned a report which found BCCI responsible for “widespread fraud and manipulation”.

The Federal Reserve in Washington was doing its own digging into BCCI’s Cayman operation. They found enough evidence of money laundering, arms financing and drug dealing to justify a joint operation to close the bank down on both sides of the Atlantic.

Advertisement

Advertisement

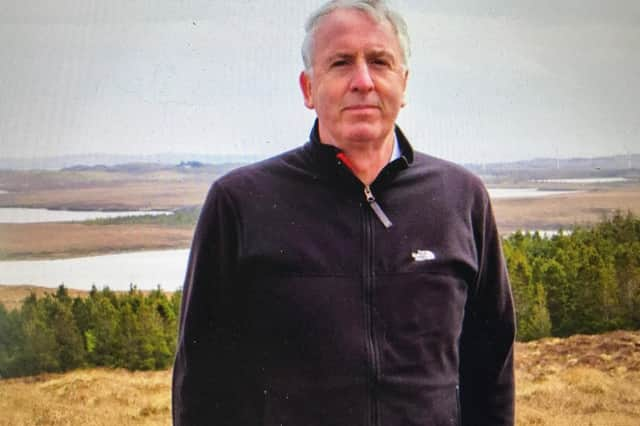

Brian Quinn was head of regulation at the Bank of England. He flew to Luxembourg under cover of secrecy and “spent a sleepless night in a hotel overlooking the BCCI Luxembourg Head Office and at 2pm the next day the court order was served and the bank’s doors closed. The US authorities closed the Florida agency simultaneously”.

The music had stopped and shockwaves reverberated all the way to Stornoway. More than a million investors were immediately affected. The ripples of BCCI ran wide and litigation dragged on for 14 years.

By then, the Comhairle had long since put BCCI behind it. The exercise in damage limitation followed by recovery was to the immense credit of all who helped ensure this was the apocalypse that never came to pass.